A country steeped in skill and craftsmanship

Alpaca fibre, often touted as the new luxury, has been on my radar a while, but as a fibre with such foreign roots, it has had to remain a distant thought. A few weeks ago however, I was fortunate enough to be invited to Arequipa, Peru to improve my knowledge of its most prominent export and meet some of the country’s top spinning mills.

For future posts straight to your inbox, sign up to STUDY 34

A yarn card from Inca Tops, one of Peru’s major spinning mills

It has been a long-term goal of mine to develop a fully sustainable and transparent supply chain. Having witnessed first hand the care and compassion of the Peruvian people towards their land, animals and ancient traditions, my trip certainly ignited a new feeling of hope.

‘Quality begins with people, not things’, a sign in a Peruvian factory I visited

The overwhelming impression I took away from my short trip was Peru’s deep sense of community, something that I think is undervalued in western society today. Leading mills like Michell Group and Inca Tops right down to the smaller players including La Republica del Tejido seek to work with local communities to preserve their knowledge and skills – and they all wanted to shout about it.

Alpaca Fibre

A Suri Alpaca, Arequipa

Peru hosts some 75% of the world’s total alpaca population, of which there are two kinds: the Huacayo and the Suri. The Huacayo, hardwearing and characterised by its fluffiness, is the more common variety, making up approximately 93% of the alpaca population. The rarer Suri (pictured above) makes up the rest and has a dreadlock type fleece with more silky fibres.

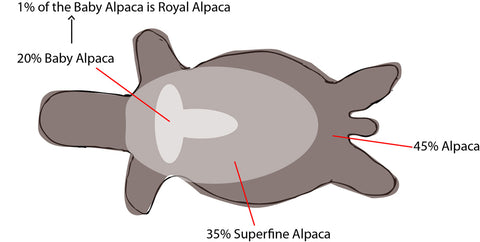

Re-creation of a breakdown of an alpaca fleece based on an explanation from Andrés Chaves at Inca Tops.

When an alpaca is sheared (once a year) the fibres are sorted by hand. These are then classified by their thickness and colour in a process that can never be mechanised as ‘the variable characteristics of the fibre can be assessed only by experienced hands and eyes’.

Fleece sorting, Arequipa

The wide range of natural colours afforded by the alpaca (not found among any other natural fibres) encourages less dying, which in turn results in less risk of damage to the environment. It is also non-flammable, has relatively high elasticity and strength, does not felt as readily as other animal fibres, has an excellent drape and natural lustre and is very soft to handle. It’s also easy to launder.

Living in an atmosphere where temperatures can fluctuate as much as 30˚C in one day, the alpaca possesses a high tolerance to temperature change, a quality which is transferred to clothing made with its fibre.

Clearly, this material packs a serious punch. But the animal itself also possesses extraordinary qualities to admire…

Sustainability

If we needed a lesson in a sustainable lifestyle, we might look to the alpaca for inspiration.

Alpaca tops, pre spinning

As one of the oldest domesticated animal species in the world, it was relocated from the more succulent pastures of the lower Andes regions at the time of the Spanish conquest, to higher mountainous areas with altitudes over 4000 metres above sea level. The alpaca was able to adapt to these less favourable living conditions and this adaptability is surely the key to its success:

‘It is precisely the reality of climate change, affecting particularly the habitat of the alpaca, that highlights one of the most interesting aspects of breeding these animals. The Andean glaciers have been shrinking faster and faster in recent decades. Weather cycles are now extremely variable and water resources will end up insufficient for the development of the impoverished high-altitude pastures. This is how the genetic adaptation of the alpaca, with its great capacity to live on poor pastures, its cushioned paws that do not damage the soil, and its peculiar manner of grazing without pulling plants up by the roots, plays an incomparable role in the conservation of these fragile ecosystems. No other animal could be kinder than the alpaca with regard to preserving the habitat of the high mountain regions of the Andes.’ - Alonso Burgos

An alpaca looks after the land it lives on and its breeder looks after the beloved animal it guards. So it is only right that we, as consumers, should treasure and value anything made from this supremely sustainable animal.

But we should also follow its example, by looking after our own living environment, and adapting to its natural limitations by taking no more from it and putting no more into it than it can naturally sustain.

This article is also available on The Huffington Post UK

Like this post? Tweet it!

Hi Denise – you raise an important issue, thank you for that! I have to say that I was not able to observe the treatment of the animals directly myself. However, in talking to the spinners and asking many of them directly about the sheering process and discussing the presence of ‘mulesing’ in the wool industry as well as watching videos of sheering on their farms, I was confident of their care. That said, it will never be as good as visiting the farms that you work with directly and viewing every process for yourself – and this is something I intend to work on. So pleased you found the post interesting! Eleanor

Thank you for a very informative article. Can I ask if you observed the treatment of the animals? Recently I’ve become a lot more conscientious of using animals for our benefit and am leaning toward veganism. I wouldn’t have a problem with the shearing of the animals if it’s handled with care, a practice that is a problem in the sheep’s wool industry. You mention the Peruvians respect their animals. Is it possible we have a truly win-win situation here?

Leave a comment